“As a staff writer for one of the largest online magazines in Egypt, I was instructed not to write about politics. When colleagues had done so, the office would find itself without power or internet for a few days.”

On 25 January 2016, the fifth anniversary of the Egyptian Revolution that ousted former President Hosny Mubarak, Cairo’s streets were empty. The fear of protests, accidentally getting involved in them and ending up with a hefty jail sentence, kept Cairo’s population indoors. Even the government had instructed people to stay inside.

Giulio Regeni, however, an Italian PhD student from the University of Cambridge, had a meeting to go to in Cairo’s district of Wust el-Balad. All he dared to endeavour was to walk three minutes to the metro station, travel four stops, and arrive at his friend’s house. He left his house, but he never arrived at his friend’s.

A week later, Giulio Regeni’s body was found on the outskirts of Cairo after his picture had taken over social media. Giulio had been tortured and killed.

On day one all we knew was that the search was over and that he had been found dead. No word of injuries. No word of suspects. No clear details that indicated why Giulio had to suffer the fate he did. Welcome to Egyptian media!

The world of Egyptian media

Media reports in Egypt are a frustrating subject. No clear figures, clandestine raids in the middle of the night, and no official comments. This is the reality when dealing with information in the Middle Eastern heartland.

Whether a mass panic in a Cairo Football stadium killed 40 or 400 people depends thoroughly on which news source one uses.

After Giulio’s murder, first described by Egyptian media as a traffic accident, more and more details emerged in the foreign press. Italian authorities demanded an investigation and an independent autopsy of Regeni’s body. According to Italian press, Egypt tried to object.

After that autopsy, the Italian press knew it was murder. Torture tactics typical of Egyptian security forces were detected.

Giulio had been alive for a few days after his disappearance. In the Egyptian media, he remained the victim of an accident.

Cartoon created by Galal Amer, an Egyptian journalist, well known for his sarcasm and sense of humour. [Image credit: Galal Amer]

The role of the foreign passport

As a foreign writer myself, I had always considered my nationality an asset for my safety. As a German passport holder, notifying my embassy if my human rights are offended would put Egyptian authorities in trouble. Egyptian journalists and human rights activists, known to be the main target of security forces establishing their own definition of “law and order”, could only hope for protection like that.

While a harmed Italian researcher makes international news; Egyptian researchers disappear frequently without embassies getting involved.

Egyptian detainees don’t have this bargaining chip. Giulio did, and he might have tried to use it. His friends believe this probably led to his murder. Maybe Giulio threatened his kidnappers with seeking help from his embassy if they continued to torture him.

The prospect of him alarming an embassy about what happened could have been the deciding factor on whether to keep him alive or not. If he had lived, his torturers could have been identified.

Giulio was not a journalist. But the foreign journalists of Cairo immediately felt the backlash. If his research is rubbing the government the wrong way, what about my findings?

Foreign journalists vs local journalists

As a staff writer for one of Egypt’s largest online magazines, I was instructed not to write about politics. When colleagues had done so, the office would find itself without power or internet for a few days.

Journalists with a much higher profile are not exempt of these limitations. Quite the contrary. The arrest of three Al-Jazeera journalists without a fair trial made international headlines and, sadly, the estimated number of journalists currently in Egyptian custody is one of the highest in the world.

Since there are no clear figures, human rights activists have a hard time making a case.

Press freedom organisation, Reporters Without Borders, ranked Egypt 158 out of 180 in their Global Press Freedom Index, while the Committee to Protect Journalists sees Egypt as the worst jailer of journalists in the world, only topped by China.

Cases such as Egyptian photojournalist Shawkan, who was held for two years before being tried, are internationally condemned. However, no effort seems to be made to eradicate such tainted stories about Egypt from the global headlines.

In Egypt, news outlets with a claim for independence are under constant threats to be shut down.

Independent online magazine Mada Masr has almost as many lawyers as it has reporters.

Their investigative journalism had one of their writers in jail in November 2015. An official charge, let alone the prospect of a trial, seemed unlikely. He was suddenly released after four days of social media backlash and international fury over the imprisonment.

But many other Egyptian journalists were not that lucky.

Numerous Egyptian citizens disappear without a trace or are accused of various other offences as a response to their political opposition to the government.

Similar things happened to the alleged killers of Giulio. According to Egyptian media sources, four men were shot when the police tried to arrest them for Regeni’s murder. As evidence of their guilt, the police released Regeni’s ID cards on social media, proving these four men had stolen them the night of his killing.

Conveniently, none of them survived to profess their innocence. Without an investigation or trial these people’s names will forever be known as Regeni’s killers because the Egyptian media decided to say so.

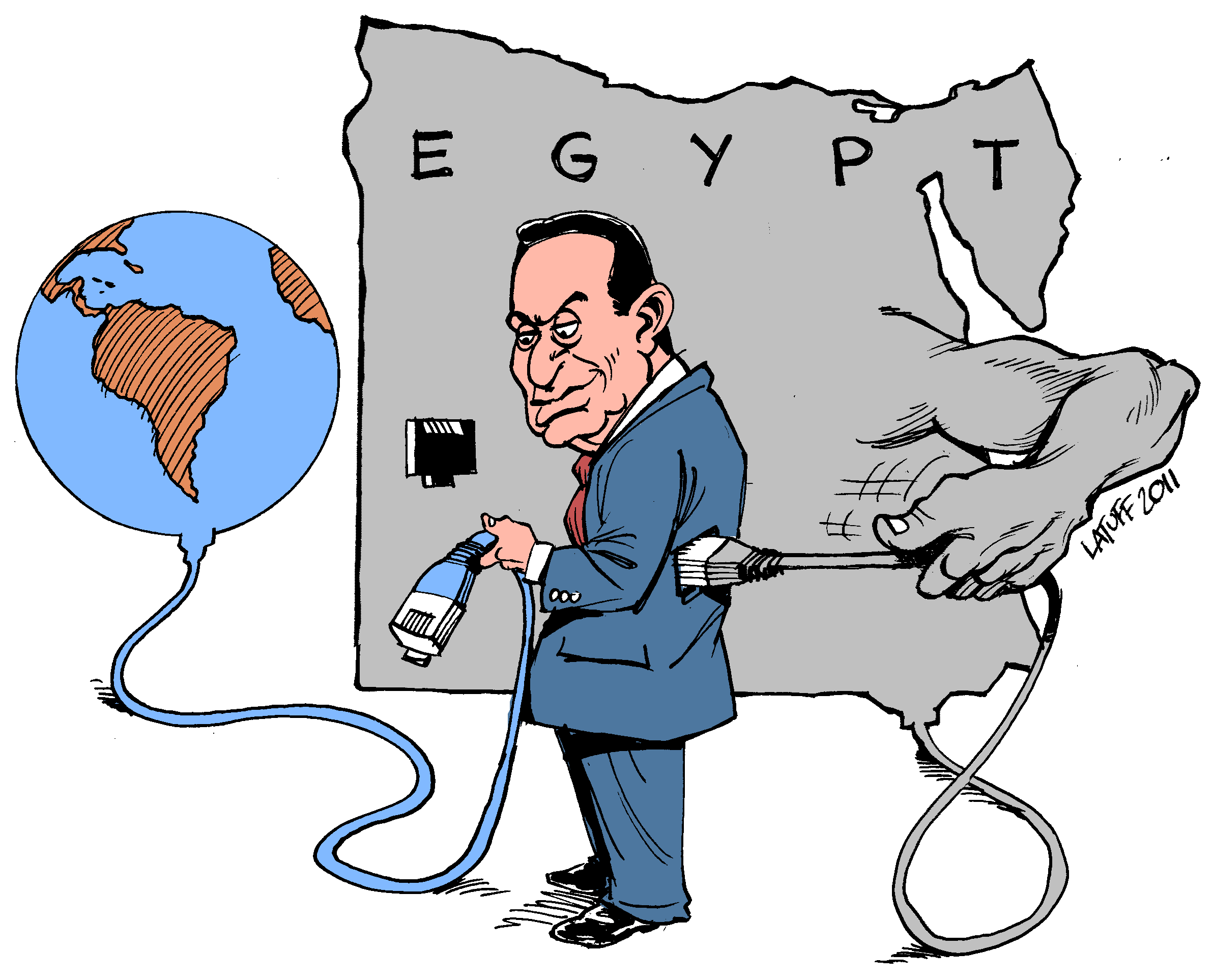

A political cartoon by Carlos Latuff depicting Hosni Mubarak unplugging Egypt from the Internet. [Image credit: Carlos Latuff]

Journalists and human rights activists live in fear

These realities have scared Egyptian and foreign journalists alike. Egypt is a safe country for tourists and most of its citizens, yet journalists and human rights activists still have to live in fear that their most basic freedom will be taken away at a moment’s notice.

Many of my colleagues had the police ring their doorbell in the early hours of the morning for an impromptu raid, some of which have been held in custody ever since.

A large number of my colleagues who have not been arrested jeopardise their freedom on a daily basis because they believe in the importance of information.

During a protest after Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi had given away Red Sea islands as a gift to King Salman of Saudi Arabia, some colleagues called me warning me not to attend the protest. They told me: “They are rounding people up and arresting them, no questions asked.”

If I had been slightly unluckier, I would have just been deported like Lebanese journalist Liliana Daoud. She was arrested in front of her 10-year-old daughter, taken to the airport and put on a one-way flight to Beirut without any luggage.

Another Irish colleague was taken to the police station, beat up for hours and threatened with a jail sentence of “many, many years”- all at his family’s and friends’ back.

Other journalists can’t even enter the country. There are prominent cases of foreign journalists simply being denied entry to Egypt.

Authorities in Egypt

The extent to which the Egyptian government is willing to make sure independent voices and opinions are muted is seen almost daily. I have witnessed anything from police officers demanding to read private Facebook messages of people in underground trains, to foreign publishing houses demanding to end the conversation in Arabic before the connection mysteriously broke. All these things speak the clear language that press freedom not only is inexistent, but that it is increasingly undesired.

In a country where “disseminating false news” is a viable indictment without any possibility of conducting independent research, journalism has become a craft rather impossible to execute in Egypt.

As a writer who has refrained from criticising the government at most times, I felt like a recent article about my fight for press freedom in Egypt could put me in danger.

As a result, I have recently decided to leave Egypt, hence the reason you are able to read this piece.