“Sometimes I just go and don’t talk about anything. I just spend time with them. It takes some time to gain trust and break the ice, and then I throw the ball in their court.”

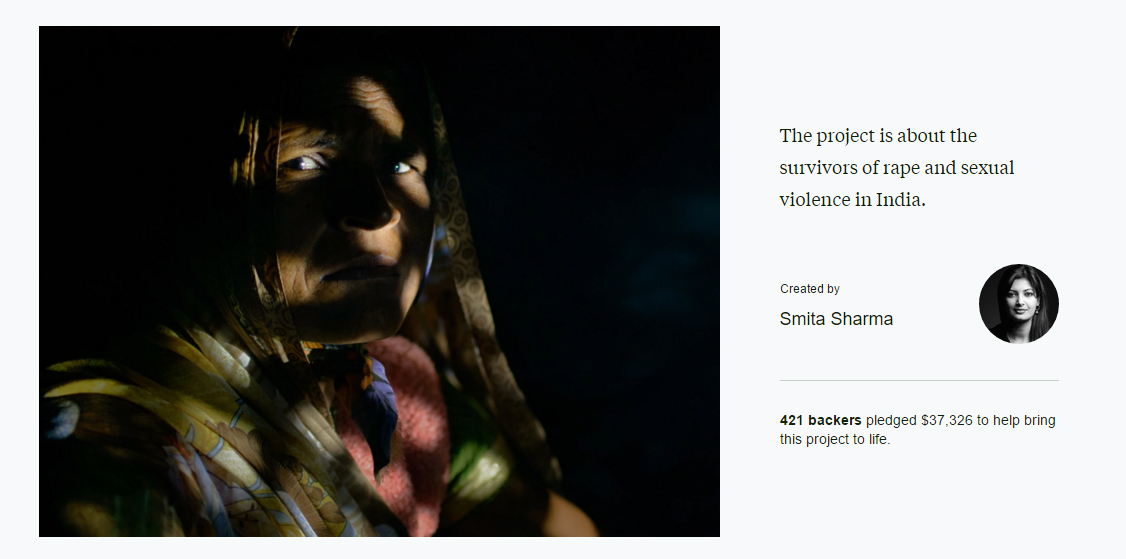

Smita Sharma is an acclaimed Indian photojournalist and documentary photographer, well known for documenting the stories of rape victims across India. She recently raised almost $40,000 from a Kickstarter campaign to continue her work as a photojournalist and produce a documentary about rape and sexual violence in India.

Here she tells IPF why she started her project and how she’s managed to overcome the challenges of her work.

I started photographing victims of rape in December 2014. I don’t know exactly why, but this is an issue that is very close to me. I think something needed to be done, because every media report on rape was just a description of the incident. You never got to hear the voices of the women who had been raped, and their families. Basically, I was curious about the people who had been affected by this crime. That’s the reason why I wanted to go and find out how they are now leading their lives and where they live. Last year, I met twenty-four women and girls and so far this year I’ve met three.

Rape is the most extreme form of violence and dishonour that can be committed against a woman. It’s also very vindictive. Many of the cases I’ve seen were done to ‘teach the woman a lesson’. I was molested by my college professor when I was 18. When I tried to speak out, I was called a spoilt child and told that I did not know how to respect my elders. I didn’t find any closure and I kept silent. But the anger stayed within me for a very long time.

When I meet victims, I never talk to them about how the rape happened. It’s not important for me to find out how things happened to them. I leave it to them. But what’s important is how they’re living their life after the crime – and whether they are being ostracized, whether they are being shamed, whether they are getting support, and if they’re getting support, then where it’s coming from. Is it within the community? Are they supported by their family? Sometimes the family is not supportive. I’ve seen a few cases like that.

I have been through situations where I felt like throwing up, literally just throwing up. I had anxiety problems and some PTSD problems.

There was a particular case where the girl became pregnant from rape and her family kicked her out of the house. She literally was left out on the road. She was just 14-years-old and pregnant. The rape was done by her landlord’s son. The girl and her family were living on the ground floor and he was living on the first floor. They knew each other and the families knew each other. One day, her mother was away and there was no one else at home. He came to the house, gagged her and raped her. Then he threatened her to keep silent. Out of fear and shame, she did – but then she became pregnant. After three months, when her family found out, she was kicked out of the house.

The girl went to a local NGO, which found her temporary shelter. Once she had her baby, her older sister came and it was then that they tried to pressurize her to marry her rapist. The local NGO filed a complaint with the police and they got the guy arrested. But it’s always a money game here. The rapist gave money to the local politician. He sent his men to the girl’s house to convince her family that she should get married to him and that everything would be taken care of.

I’ve had one or two cases where I’ve met the mothers of the perpetrators and when I ask them questions they tell me: “My son is innocent. The girl trapped him.”

I spend a lot of time with the girls and women I take photographs of. Sometimes I just go and don’t talk about anything. I just spend time with them. It takes some time to gain trust and break the ice, and then I throw the ball in their court. I let them decide what they want to tell me. I’m really honest with them and tell them why I’m there.

Once a city girl like me goes to the village it spreads like wildfire, so everybody knows about you. The village leader has his men all around and they’re like spies. They have this idea about the ‘honour of the village’ and they don’t want any negative news to go out of that village. That’s when it gets very difficult to do my work. And as a woman I have to take care of my own security. Most of the time, I don’t tell them I’m a journalist. I go there pretending to be a health worker, as somebody there to do a bit of research on the health and sanitation of the women. Once you tell them you are there to find out whether they have access to toilets or to talk about pregnancy, they accept that. It’s also a way for me to protect the families of the women, because I don’t want to isolate them in the village. I will come out of the village after five days, but they have to live there. Instead of going to one house, I go to ten different houses. Within those houses is the main house where I work and the victim’s family. I spread around a bit so they feel comfortable, like they’re not being targeted or isolated.

The stories I hear do have a psychological effect on me. Anyone would be affected. If I’m not being affected, then there’s something wrong with me. I have been through situations where I felt like throwing up, literally just throwing up. I had anxiety problems, and some PTSD problems. Sometimes when you come back home you don’t feel like eating and when you see friends around you who don’t realise what you have seen, you can feel a disconnect.

Rape is a huge problem, but to tackle it we can start off by talking about it and raising awareness, by having a discussion within communities – even within schools and colleges. People need to talk about this. Also, we need to address how men are treated at home. I feel that a lot of men in this country are treated in a very insensitive way. They’re always told that they’re not supposed to cry and they’re not supposed to behave in a certain way. There is a lot of pressure to be masculine.

I went to a village in Utter Pradesh and I was watching seven-year-olds in a co-ed school. They were all sitting in rows and there were separate rows for boys and girls. I asked the students why they were sitting separately.

One seven year old boy stood up, very proud, and told me: “The girls are inferior to us. Why should we sit with them?”

If a seven-year-old can say this to me, you can imagine what he must be taught at home. And who is teaching him this? Either his grandmother or mother. This is a patriarchal culture, but it’s not just men who are responsible. Women are teaching this to their sons. I’ve had one or two cases were I’ve met the mothers of the perpetrators, and when I ask them questions they tell me: “My son is innocent. The girl trapped him.”

This is my personal project and whatever savings I had, I’ve now used them. For the past year I’ve been working out of my own funds, but now I’ve reached a stage where if I want to continue – I need to travel. There’s a lot of costs involved, from travelling, to getting a driver to come get you and staying in a safer place – there’s a lot of logistics involved. I need to support myself; this was the reason for starting my Kickstarter campaign.

I’m also going to use some of the money for three organisations. One has a project to give bicycles to girls and I’ll be donating some bicycles to them so they can distribute it to girls who drop out of schools because of sexual assault. The other two do a lot of work across north and south India. I’m going to produce a ten minute film, which they will show through a projector to communities all over India. It’s going to be about the survivors themselves. I’m sure that when people see the faces of the victims and hear them talking about their experiences, it’s going to have some effect.