“FGM is like a life sentence. Every day is a struggle. There’s no aspect of your life that hasn’t been affected by it.”

Hibo Wardere is an FGM survivor who has gone from being a refugee to a leading FGM activist. She fled Somalia’s civil war at the age of 18; when she got to London, United Kingdom, a feeling of immense freedom flooded through her. Not only had she found safety from conflict, but she now could live knowing that her future children would never go through the horrors of FGM.

Unlike Hibo, there are many women and girls trapped in a cycle that sees generation after generation undergo the practice. This week, UNICEF estimated that there are over 200 million victims of female genital mutilation around the world, a figure 70 million higher than previously thought. In Somalia alone, 98% of women between 15-49 have been through FGM.

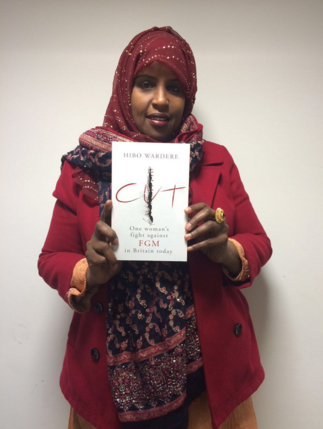

Hibo Wardere with her memoir, Cut, which will be published in April this year. Photo credit: Hibo Wardere

“It took me over four decades to even begin to talk about it. Can you imagine what it’s like for women who don’t even speak the language?”

Now she’s trying to put an end to the practice by working as an FGM mediator in London – and she’s using art to spread her message. Last year, she had her portrait painted by artist Emma Scutt for a collection depicting FGM survivors. The paintings, which also include portraits of FGM campaigners Leyla Hussein and Alimatu Dimonekene, proved so popular that they are being exhibited for a second time in libraries across North London.

Artist Emma Scutt said: “I went to a talk by Hibo on FGM, and was completely blown away. She was so confident, funny and moving, and I was captivated by her face. For all their femininity and dignity, it’s such a dreadful thing that’s happened to these women. I thought that making this art would be my way of making people aware.”

The portraits, which were painted from simple photographs taken by Scutt, are raising awareness of FGM within the local community. For Hibo, the experience of being painted was also an opportunity to reflect on one particular woman who had put her through the pain of FGM.

From left to right: Alimatu Dimonekene, Hibo Wardere, Emma Scutt, Leyla Hussein and MP Stella Creasy. Photo credit: Emma Scutt

“When Emma came to my house and was taking pictures, she asked me to think about something. I remember I looked out of the window and all I saw was my mother. She captured that, and when I went to her house to see the portrait I burst into tears. I literally see my mum in that picture.”

“Looking back, I do really feel that it wasn’t [my mother’s] fault, what she did to me was her way of understanding motherly duties. She did love me very much. All I could think about was her and how she wholeheartedly believed it was for my own interest.”

Hibo spends her time visiting schools and doctors to talk about the debilitating effects of FGM, and how it can be prevented. She believes that education is the key to eradicating the practice, and that the British Government must do more to integrate the issue into school lessons.

“Every school that I’ve been to so far, all the children who come from those communities don’t even know FGM exists.”

“Education gives girls the right to say no,” she added. “All it takes is a 35 minute lesson. Right now, it’s just up to headteachers whether children should know about this.”

Hibo Wardere

When Hibo was seven her mother held her down while a woman from the village cut her with a razor blade which was still covered in dried blood from the previous girl.

“From that moment on, she was no longer my mother.”

“What you go through is unimaginable pain that will last a life time. The only way I can compare FGM after it’s been done is like when an earthquake happens and the tsunami follows. For me the tsunami was my emotions which I was drowning in and no one to help me swim through it.

“As a seven year old who has gone through FGM let me tell you how this horrendous, barbaric, medieval practice has left me with a life sentence of pain.”

“You don’t have a connection to your own part of your body because they ripped your clitoris. Imagine been told that you can’t have children because of damage they have done to your reproductive organs. You also suffer with constant infections, more than the normal woman because they have cut off completely your vaginal lips that protect from germs entering you. It’s like your eye lids being ripped off and you suffer with dryness too.

“This beautiful country that I call my home today and my children who were born here, all of them… I cannot imagine this taking place in this country, and the government isn’t doing enough.”

“I just want to go to schools and educate the staff by giving them a better understanding of FGM. Together we can achieve our main objective which is to prevent FGM happening to innocent young girls.”

Leyla Hussein

Leyla was born in Somalia. She was cut when she was seven years old. Four women held her down while a fifth cut her. She screamed for her mother to help her, before passing out.

Leyla is a Community Facilitator at Manor Gardens, where she now runs the Dahlia Project which she set up in 2013, the only counselling service for FGM survivors in the UK. Her documentary on FGM in the UK ‘The Cruel Cut‘ was shown on Channel 4 and was nominated for a BAFTA in 2014.

“My struggle has focused on FGM, a crime that affects 125 million women in the world. It has focused on FGM because in the UK alone, there are 170,000 women who have undergone it, and tens of thousands of girls at risk every year.

“FGM for me represents all that is wrong about the way this world treats women; as a commodity.”

“I refuse to be judged only by how good a wife or a mother I will make. There is nothing wrong with either of those roles, but a woman should be allowed to choose neither. I refuse to give up my basic human rights just because I have a vagina. I refuse to nod and say ‘things are getting better’.

“Because I have the privilege to speak, I have to roar. I will continue to roar for as long as there are women who have no voice.”

Alimatu Dimonekene

Alimatu was born in Sierra Leone. She was cut when she was 16. Her six-year-old sister and two-year-old cousin were cut at the same time, in different rooms. She vividly recalls the day she went to her grandmother’s house, assuming it was just a family visit.

Then she heard the sound of drums outside which she recognised as part of the FGM ceremony and realised what was about to happen.

She was stripped naked and held down by members of her extended family, while a woman from the community (who was drunk) cut her with a knife. As part of the ritual her open wounds were daubed with a herbal ointment, her legs bound together with cloth, and she was left alone for days to heal.

Dimonekene says that afterwards “all the colour went out from my life”. She had been well educated, with parents who told her she could go to university and achieve whatever she wanted in life. After the FGM she questioned why she had been educated and given a taste of another life, if her family had always intended for her to undergo the tradition of FGM.

“What was the point? It was cruel.”

One of her cousins bled to death not long after she underwent FGM.

The paintings will be exhibited in Waltham Forest until March 2016. For more information, visit Emma Scutt’s website.