“I’m not creating a discussion saying you have to accept women who have hair, I’m saying you have to accept women for choosing what they want to do. Period.”

As a first-generation Pakistani-American, 20-year-old artist Ayqa Khan straddles two very different worlds. Based in New York, Khan spent a lot of time in her mother’s beauty salon, learning how to wax and thread for local South Asian women. But in school, life could often be a minefield of cultural contradictions, where “expressing yourself” meant side-stepping the traditional values so strongly touted at home.

“My mum and dad are pretty conservative,” said Ayqa. “When it comes to dress code, I can’t wear shorts and tank-tops. When you’re in high school and all your friends are white, they’re like why are you wearing pants when it’s 90 degrees?”

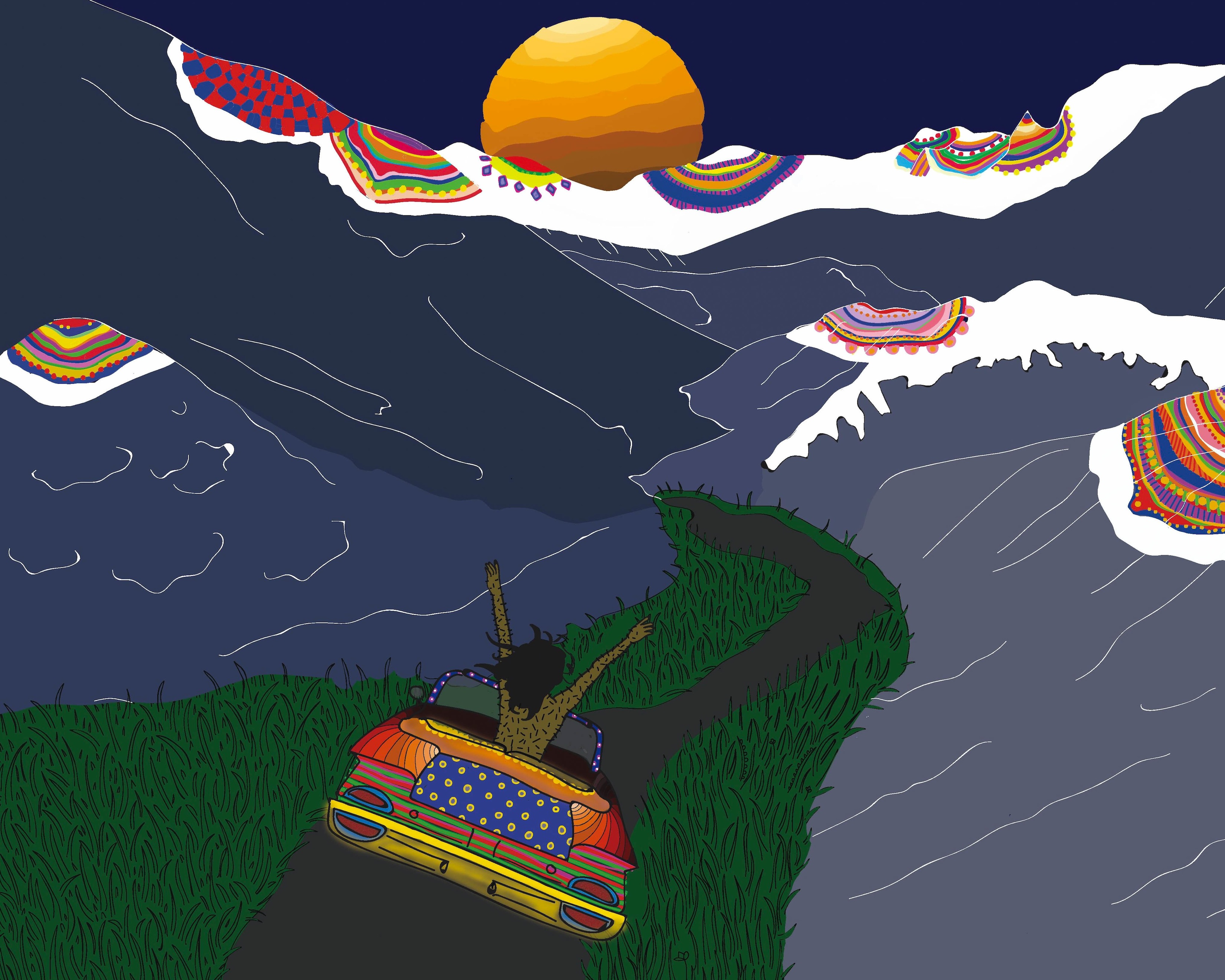

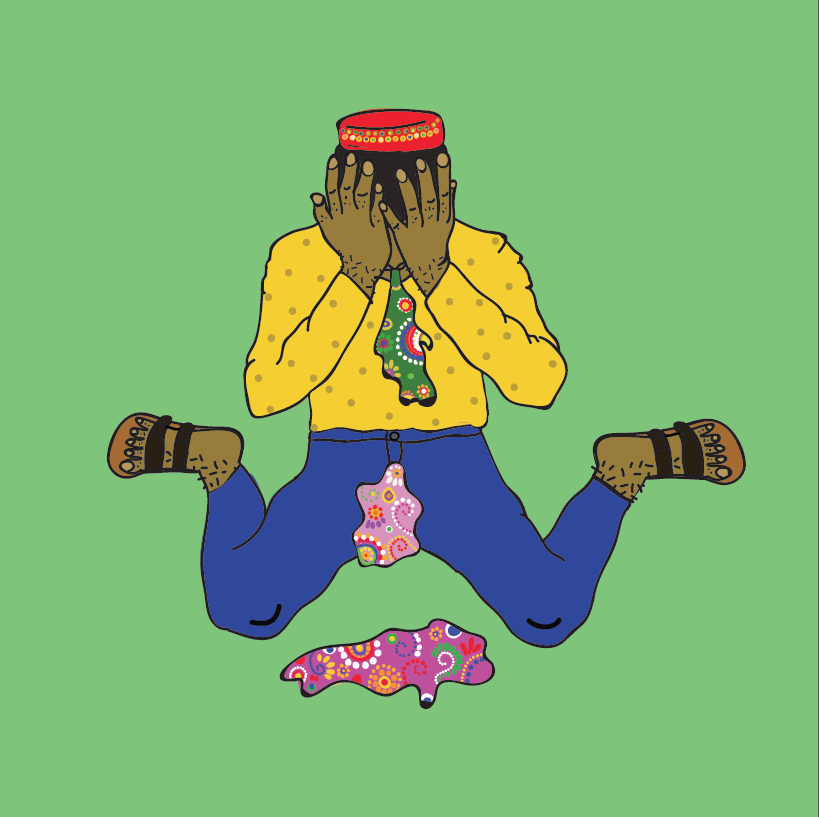

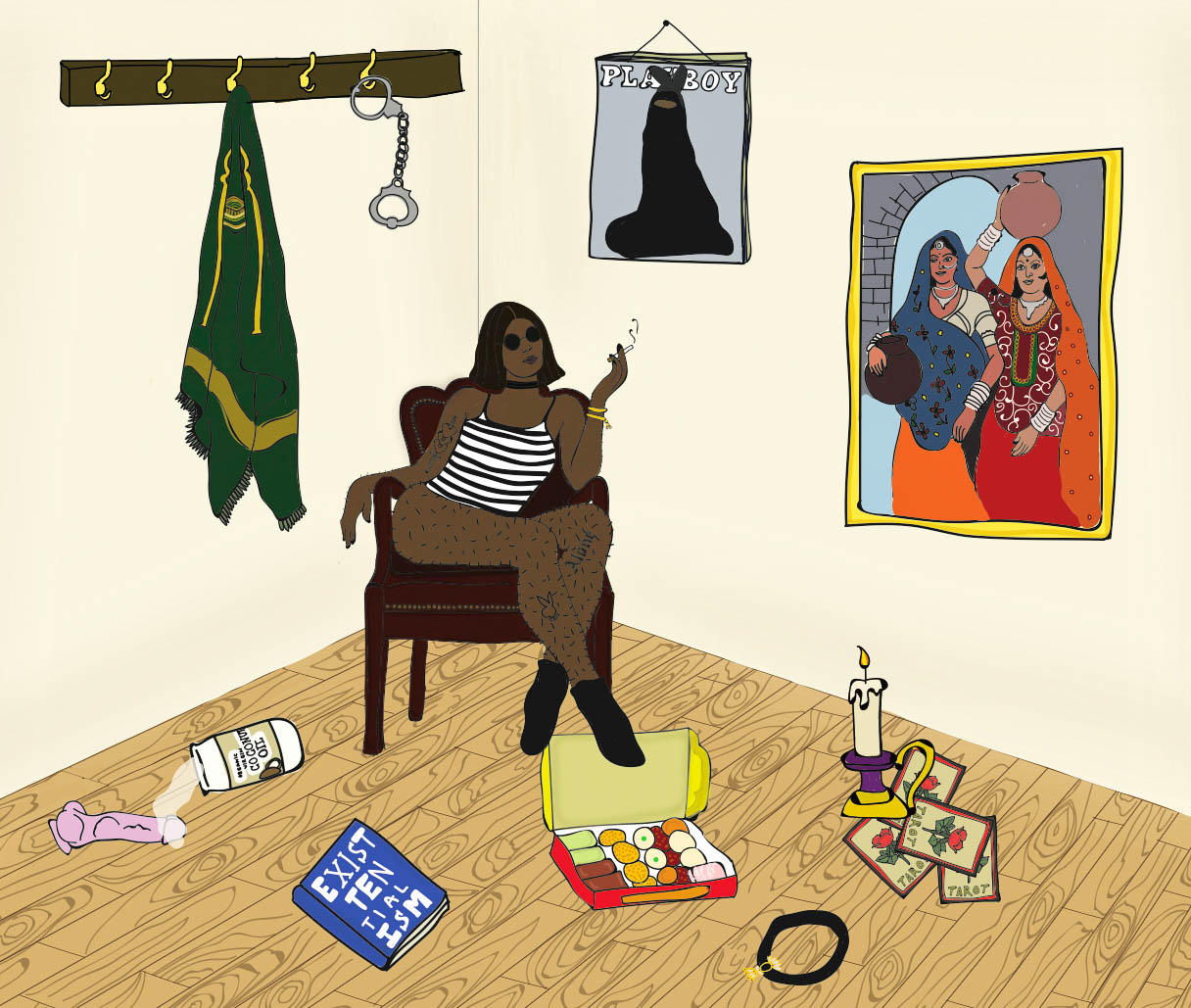

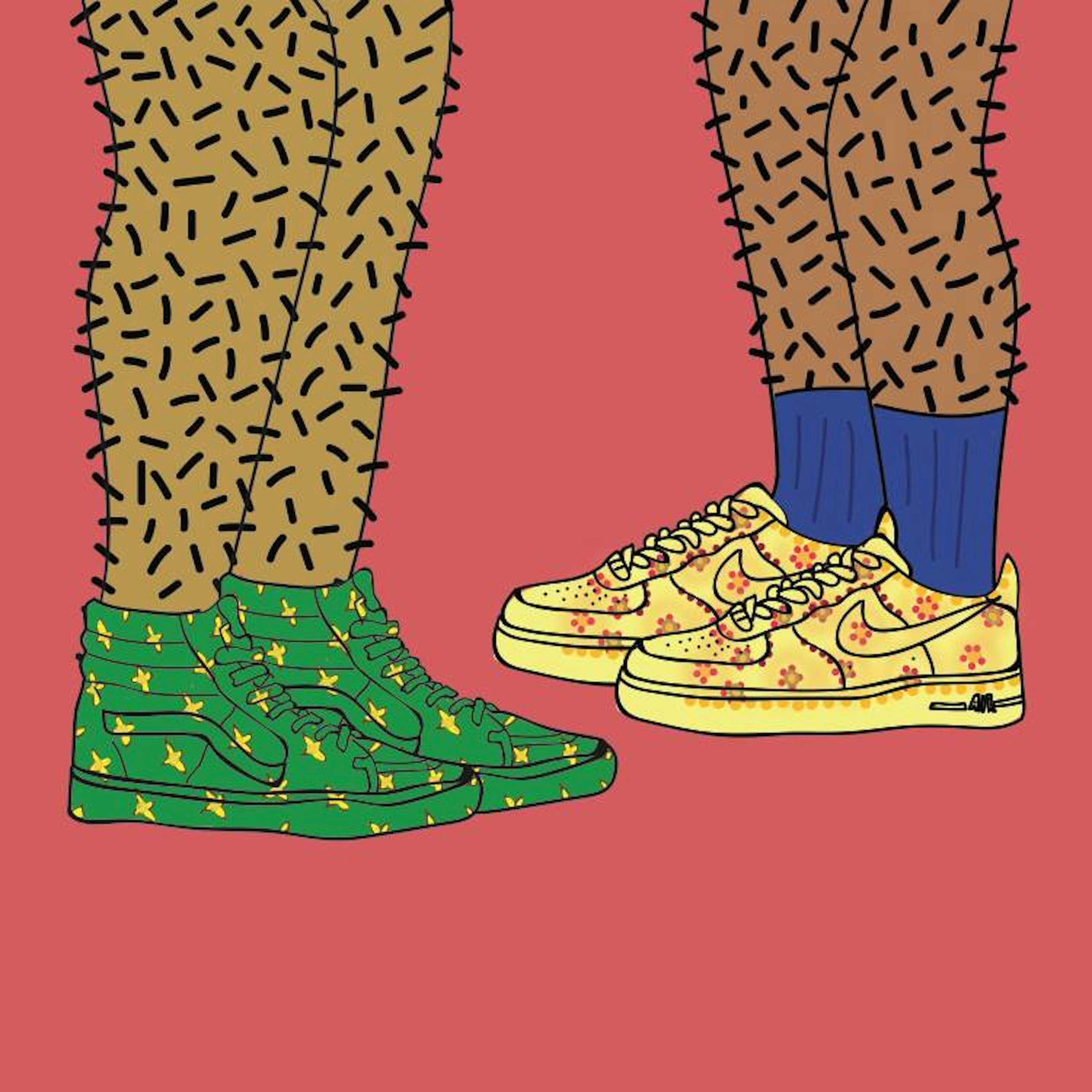

In her latest series of illustrations, Ayqa explores the first-generation immigrant experience, combining her love for traditional henna and textile patterns with a wholly unconventional approach to Asian feminine beauty.

“I had my parents and my siblings telling me that my body hair is disgusting and unfeminine, and that I looked dirty. That affects your mental health.”

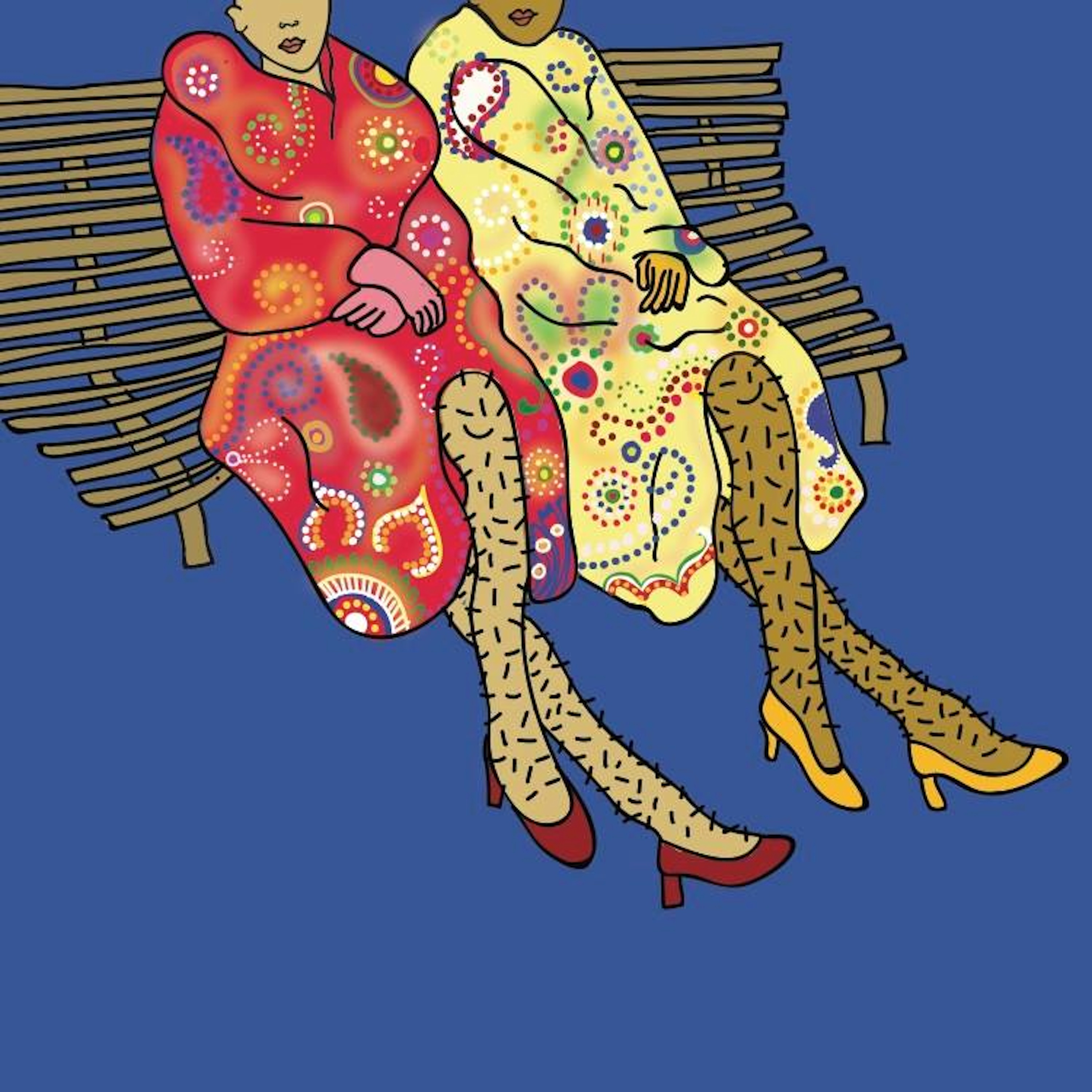

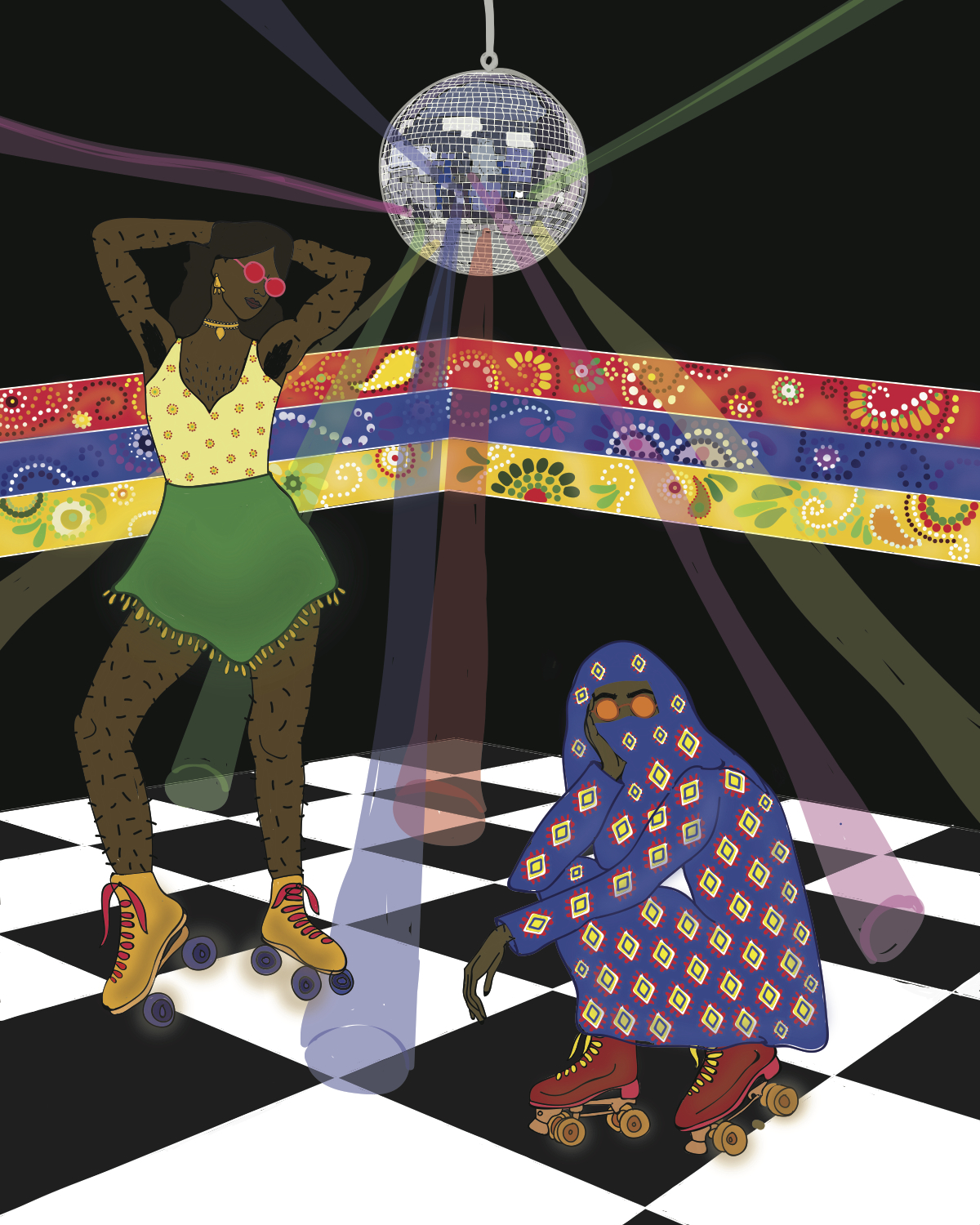

Her art features women dressed in sneakers, niqabs, bangles, swimsuits and birthday suits, all covered in thick black body hair.

“I’m sure a lot of (South Asian) girls can relate to this: we have a lot of body hair,” she said. “My body hair in particular is very thick. I had my parents and my siblings telling me that my body hair is disgusting and unfeminine, and that I looked dirty. That affects your mental health.”

“What am I taking too far, when this is my reality?”

For Ayqa, her art asks young women like herself to question why they remove their body hair in the first place.

“Just breathe, it’s okay,” Ayqa said, referring to the message behind her work. “You don’t have to feel this pressure to look a certain way.”

Khan’s favourite piece is ‘Disco Baby’. She says: “I love the colours. But also, it was very important for me to show two Muslim girls. I used to go to the mosque all the time, and a lot of the girls who wore hijab would always pick on me. It was very important for me to show a diversity in friendship here.”

With no formal training in art, Ayqa began uploading her work to Tumblr last year. While some have called her illustration “gross” and “taking it too far”, she has also received hundreds of positive messages from young girls who feel emboldened by her images.

“I feel so blessed to have these (positive) comments,” added Ayqa. “I’ll have so many days where I’m really depressed, questioning if what I’m doing is the right thing, and I swear, I’ll always get a message… it feels like a sign to keep going.”

“I drew a lot of inspiration from lack of diversity. It’s not fair to constantly be exposed to work that I can’t relate to.”

Although she has a strong support base online, Ayqa said it’s much harder to find the same level of acceptance in the real world, particularly when it comes to her own relatives in America and abroad.

“My family in England is conservative, and I know that they’ve come across my work,” said Ayqa. “I don’t know what they think. I get nervous thinking about it, because I feel like I’d have to defend myself, and I don’t want to.”

For Ayqa, it has also been a struggle to find support within the art scene in New York, where South Asian women are under-represented and often linked to racial and religious stereotypes.

“A lot of artists (in Brooklyn) are white,” explained Ayqa. “There were lots of women preaching feminism and doing all this work that had zero diversity. I drew a lot of inspiration from lack of diversity. It’s not fair to constantly be exposed to work that I, and other women, can’t relate to.”

In the face of a frustrating lack of diversity, Ayqa hopes to “make movies about girls like me, that younger girls can relate to”, as well as artwork that talks about having an online presence as a Muslim woman, identity, racial issues and Islamophobia.

“I’m not trying to make commentary on something bad that’s happened,” said Ayqa. “I’m showing you my reality, and I’m showing you a future that I want because I think we can get there.”