“Although it was the lack of awareness regarding menstruation hygiene that precipitated the Mukti Project, we realised that empowering women is a much more complex web of intertwined prejudices and lessons taught to young girls.”

Young girls from the villages of India are often forced to quit school halfway through their education. Why? Lack of knowledge on how to deal with menstruation.

Now, two young women have stepped in to break the taboo surrounding periods in Mumbai. Through the Mukti Project, Sarva Damani and Ayesha Alam are working to educate people about menstrual hygiene and keep hundreds of girls in education. Both the women were part of the Teach for India fellowship at the time, which places college graduates in low-income schools as full-time teachers, and explained how they got drawn into the reality of their lives.

Speaking to the IPF, the girls said:

“No matter how hard you try, you inevitably end up forming emotional bonds with your students and their families. Who would have thought that women in a city of Mumbai are still sticking to age-old alternatives of old rags?”

When they started asking their students and mothers about what they use during their periods, they were shocked to learn that many of them were using old saris. This was further exasperated when they learnt that the girls and women had no procedure to ensure that the cloth is dry, sanitised and bacteria-free before reusing it.

More questioning led to the realisation that many female students were dropping out of school between grades seven and ten. Thus, the Mukti Project was born.

Here, the IPF speaks to Sarva and Ayesha about how the Mukti Project evolved from focusing solely on menstrual taboos, to issues surrounding gender inequality and safety for women in Mumbai. Looking beyond the much-needed classes and workshops that they run in schools and community centres, the IPF found out about some of the wider issues relating to lack of menstrual awareness in India.

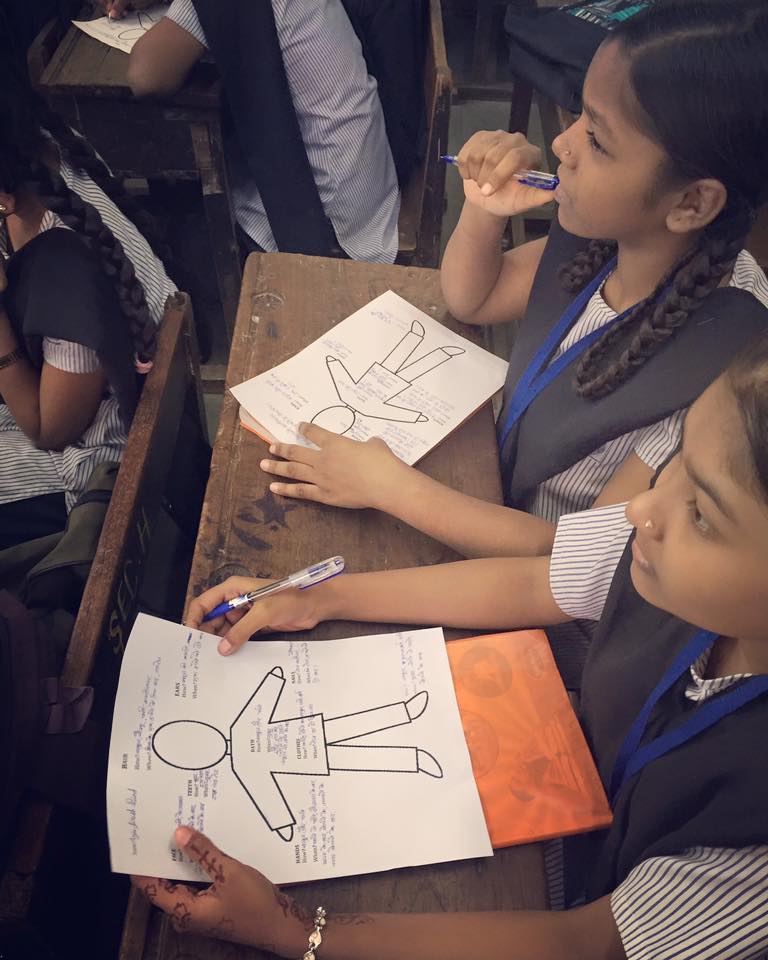

Only five out of 32 women in this introductory Mukti workshop said that they use sanitary napkins during their period. The rest use alternatives, such as old sarees and spare cloth which aren’t sterilised. [Image credit: The Mukti Project]

The Mukti Project: Challenging the shame through myth busting

All the negative associations that we teach girls to harbour when on their period makes for such a sad state of affairs. During our classes we address every myth and taboo we have come across:

- “Don’t have a bath during your period” was recommended due to the existence of communal baths in olden times.

- “Don’t jump around, sit in one place” was said because of the chances of the cloth pad shifting.

- “Stay inside the house” was due to the fear of staining.

The ugly truth is that even though the context and time has changed, these myths have passed down generations and considered to be the absolute truth.

The absolutely ridiculous ones, like “don’t touch papad, pickle, plates”, are the ones that we tell students to really question and see if there is even a little, if any, rationale behind it. When they fail to come up with an explanation for these taboos, they automatically see that there is no relevance and no truth in them.

Through debunking the myths, we have encouraged students to question; question what society expects of them. Does it have any reasoning or is it just something that has been derived from a whim? We need to encourage children and adults to question; that is absolutely imperative. We are losing the ability to question, which is sad because that has been the impetus to every revolution.

Mukti starts its second batch of women empowerment workshops with girls in Geetanagar, Colaba, Mumbai. [Image credit: The Mukti Project]

Making a difference in small ways

When conducting classes with students in school one day, a teacher as old as me attended the Mukji class.

It was the class which focused on positive goal-setting regarding, not only professional aspirations, but personal aspirations. We spoke about long-term planning and being deliberate about life-decisions, instead of impulsive.I told them that I have a list of things I want to achieve before I settle down, criteria for who I marry and when I want to marry.

I wanted them to know that it’s okay for girls to have dreams and aspirations, even though their community might teach them otherwise.

On my last day in school, that teacher came up to me and told me that, at the time, she was facing a lot of pressure from her parents to get married. It was because of that one class that she had the courage to tell her parents she was not ready; that she did not like any of the boys she had met. More importantly, that she realised she was not wrong in feeling these emotions. I think that is definitely a memory I hold closest with regard to the Mukti Project.

I conducted a workshop on safe and unsafe touch, domestic violence and physical abuse. We had images of quotes; one of these quotes was from a placard held during a protest that said: “It’s a dress, not a yes.” We had a discussion around what this means and a debate on whether a woman’s clothing determines whether she is at fault if she is raped or molested.

A couple of months later, I was discussing Delhi’s Nirbhaya rape case with my classroom, boys and girls included. One male student stood up and said: “Didi (sister), many times girls wear short clothes and this encourages men to act in an inappropriate way.”

At that point, a student, Jansi, who had been present in the Mukti Project’s workshop, sprung up from her seat and said: “It’s a dress, not a yes.”

She explained to the entire class that a girl’s clothing should have nothing to do with another individual’s behaviour towards her. It took me a couple of seconds to stop smiling because it was definitely one of those moments where you feel like you’ve made an impact.

4 out of 5 girls in India drop out of school at the onset of their menstrual cycle. [Image credit: The Mukti Project]

‘Menstruation is unclean’

Menstruation being unclean and women being made to feel “impure” is one of the most detrimental effects of the taboos around this.

Telling young girls that they need to hide their period and making it seem like they have perpetrated a crime, shapes their self-worth.

We ask students whether there would be a foul smell if I cut my veins with my blood oozing out. The obvious answer is no. But what if I am left lying in a pool of my blood for five or six hours? There will be a foul smell, which is the bacteria getting activated. It is exactly the same with period blood.

The entire reason for getting your period is that your body is getting rid of extraneous tissue and blood. It is baffling to us how this entire “unclean” theory even came into existence.

Our plan for the next year is to have a curriculum for the boys as well, in order to raise awareness about puberty and gender equality in particular.

We want to include menstruation as part of the boys’ curriculum in order to create awareness about the normalcy of menstruation and lack of any reason to be ashamed of or hide it.

To find out more about the Mukti Project, visit their website and like them on Facebook.