“You think its easy for me being here, instead of being in my home? I don’t want to die now. I want to live longer. And that’s why I’m here.”

“I will build a great, great wall.”

As we commence into the dawn of President Donald Trump, it seems we are witnessing a purging of the United States, with seven of the world’s countries already banned from entering the country.

While Trump rants that Mexico has brought gangs, drug traffickers and cartels into the US, he has failed to acknowledge that the majority of those who cross the border are not, in fact, Mexican. They are from Central America, and are currently in the wake of their own refugee crisis, which a “beautiful, southern border wall” will do nothing to change.

New to Mexico City, a friend asked if I would like to work in a shelter dedicated to housing men fleeing from gang violence in Central America. Standing outside the shelter for the first time, a buzzer on an anonymous looking tin door gave way to a block of stairs. Tentatively, I took them, while trying to stifle visions of a room, in which people sat in troubled silence, running through my head.

Faces of Tochan

At the top of the stairs lay a scene of people rummaging around a kitchen preparing lunch. A pan containing sizzling chicken spat oil, tortilla after tortilla was stacked within whicker baskets, still steaming from being taken off the grill, as two giant bottles of Coca Cola were ceremonially laid upon the table. People were laughing, shouting and sweating as whole chillies, limes and salt were placed alongside knives and forks. The meal contained so much salt, that a silent thought echoed through my mind:

“This is how you would kill a small child.”

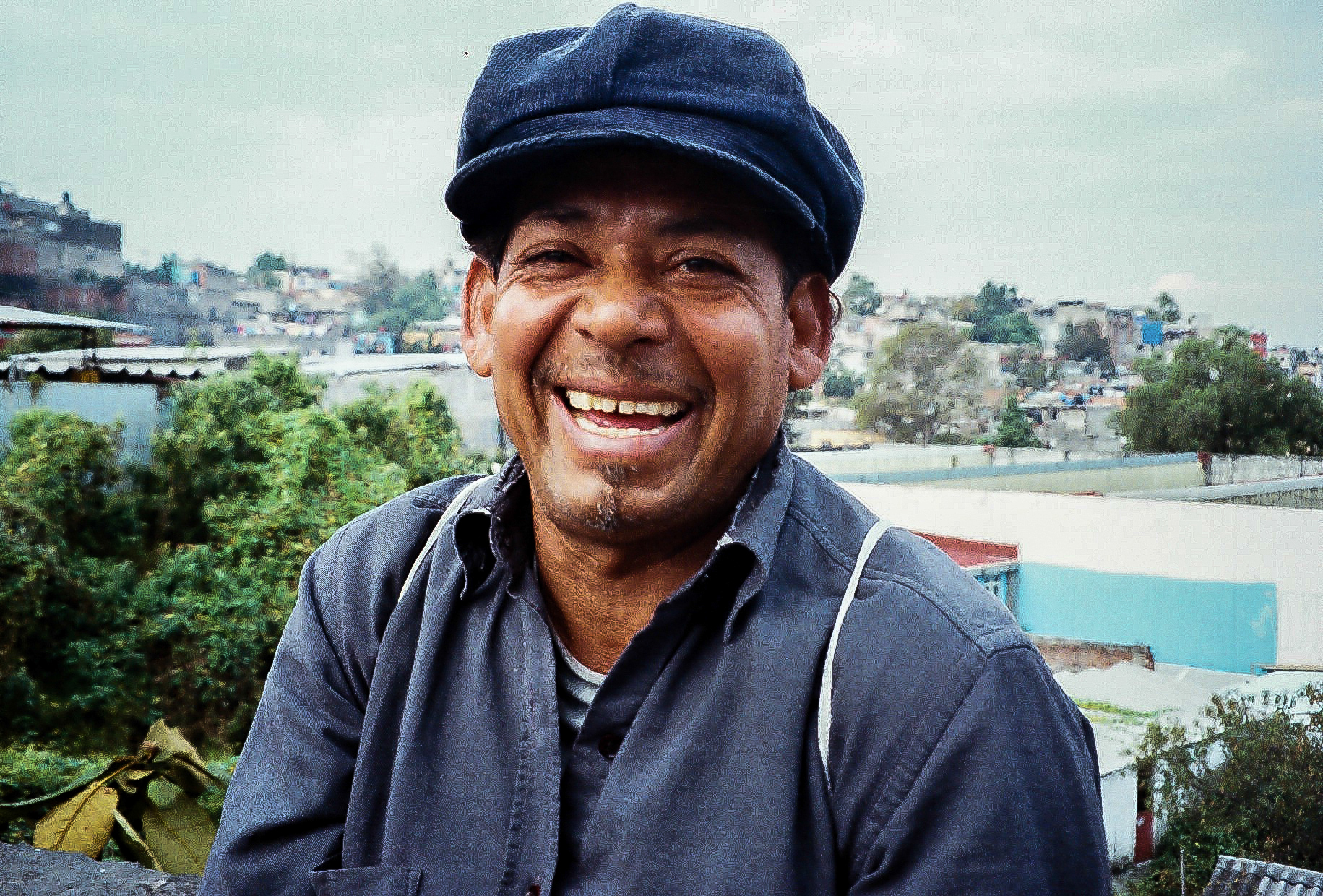

From left to right: Ender; a trained chef and restaurant owner who left El Salvador when his brother-in-law started attacking him for his sexuality, Manuel; crossed the U.S. border from Honduras but was then deported by the authorities, and Javier; who fled from Honduras and fought for a year trying to acquire legal papers in order to study. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

One boy, whose name I later learned was Emiliano, sat in the corner behind an old Windows computer, frantically alternating between two buttons while shouting, “Pinches Zombies!” – fucking zombies. He was not sad, nor depressed, he was waiting for his lunch.

Emiliano, 18, from Honduras, who spent his time either playing zombie video games or writing lyrics about migration. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

Victor, from Honduras, was given permission to stay permanently at Tochan in exchange for being its resident handyman. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

Jose-Antonio, 17, from Honduras. A self-proclaimed romantic. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

A safe haven from gang violence

Central America’s Northern Triangle (Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador) currently ranks as one of the most violent regions outside a war zone. Data collected by La Pensa states that citizens of the Northern Triangle pay more than $651 million annually to gangs that otherwise threaten violence and death.

In 2016 alone, more than 408,000 apprehensions were made at the US border, while an estimated 400,000 migrants are estimated to currently be in transit from Guatemala to Mexico. While each person at Tochan had a unique story as to why they initially decided to migrate, every story shared the same premise: gang violence.

Watching Cartoons in the dormitory. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

“See I had a business in my country, and they [the gangs] wanted me to pay them every two weeks. I had to pay otherwise they would kill me. They gave me 24 hours to pay five thousand dollars. In 24 hours where am I gonna get that money? So I left my county, got to Guatamala, and then to Tapachula, Mexico.”

Jose-Antonio, 17, from Honduras: “I did not want to work with the gangs, so they said they’d kill me. They gave me three days to leave, so I left”. He was able to find work at a local Tortillería and lived at Tochan until another shelter offered him a permanent place and access to education. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

With no other choice, Leonel travelled to the US, taking “La Bestia” (The Beast); a train used for cargo that passes through Mexico. He said the journey was so difficult that he would cry because he couldn’t bear the cold or how much his feet hurt.

Leonel, 21, from El Salvador, who was forced to migrate after watching the murder of his father. “The mareros (gangs) ask you for money and if you don’t give 100 pesos daily, for example, they kill you. They act like that with everyone in El Salvador. One may try to sell sweets in the streets but the mareros are going to ask for their share”. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

He knows that if he returns to El Salvador, he will be killed. But making a meaningful life in Mexico continues to prove impossible.

“I want to return to El Salvador and live there, but I just can’t because of the mareros.”

When I commented on how strong he was through everything, he simply said: “Well yeah, truthfully, one has to be.”

Leonel with Tania, the daughter of another resident, who he met at Tochan. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

Holding onto aspirations

Despite what they have been through, the residents of Tochan continue to hold onto their personal aspirations. Amid the extreme violence in their homeland and the hostility of Mexico’s economy – where the most prosperous job available was dish washing – many still dream of starting small businesses, making music or, in some cases, simply living a life without violence.

Ender is a trained chef. He successfully opened and ran a restaurant in El Salvador before being forced to migrate due to hate crimes and attempted murder against him because of his sexuality. When he appeared before a judge, he was told he had to leave his home and change his ways.

Rossman, from Guatemala, who lost his leg after being pushed off La Bestia: “Yes, I am lucky.” [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

Now in Tochan, he described his current ambitions:

“Achieve shelter and start again. Reopen a restaurant here in Mexico. Introduce Salvadoran cuisine. Salvadoran cuisine is among the best in Latin America, so I want to make it known here in Mexico.”

Regardless of his talents and ambitions, without legal papers, Ender is confined to living in shelters and making small amounts of money from part-time jobs, unable to move forward with life in Mexico.

“El Gusano”; the caterpillar. Named as so because he believed caterpillars were born from butterflies and could travel freely without borders. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

Looking ahead

Although Tochan is a place where people take pleasure in activities such as football or cooking, it has also become a place where people sit out their days with little to do, wondering what comes next.

Unable to find work, some men sleep all day, preferring to be asleep than to face the uncertainty of their present situations.

Communal cooking at Casa Tochan. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

“If I was at home, I wouldn’t have a job because people put a gun to your head and tell you, ‘If you don’t find me this money…’ They kill you. I don’t want to die now. I want to live longer. And that’s why I’m here.”

Christianity and Chelsea Football Club; reasons to go on for

one Guatemalan refugee. [Image credit: Francesca Mills]

A wall on the border won’t change the desperation that drives people to migrate; all we are set to see is more violence and hate crimes.